Start by Not Being a Terrible Software Engineer

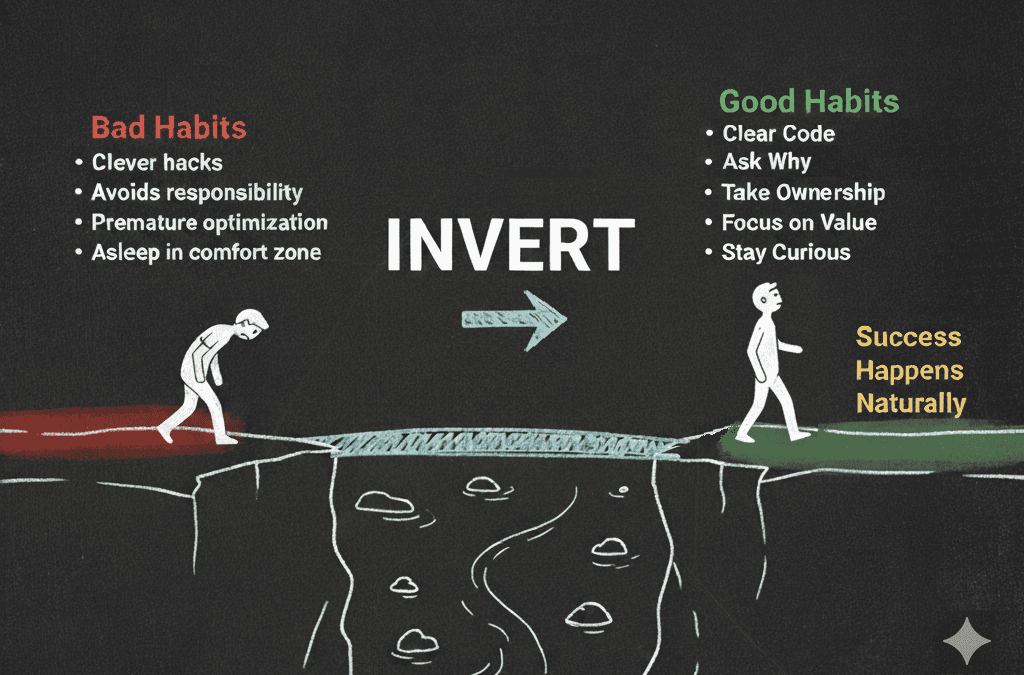

Summary ⇒ Aiming to be a 10x developer by chasing every new tool and content is a recipe for burnout. A more effective strategy is inversion, focus not on being excellent, but on systematically avoiding common failures. For an engineer, this means prioritizing the elimination of bad habits that create poor code.

Forget becoming the mythical “10x developer.” The constant and never-ending stream of new tools, content, and courses is mostly a distraction, and chasing every other trend leads to burnout, not excellence. Instead, there’s a simpler and more consistent way to build a solid foundation and ensure career growth: inversion.

This idea, popularized by the legendary investor Charlie Munger, is simple and brutally effective. Instead of asking, “How can I succeed?” ask, “How will I fail?” and then avoid those behaviors and actions. For example, Munger used this approach in his job as a military weather forecaster by asking, “How can I kill these pilots?” The answer: there were only two ways, let them run out of fuel or fly into icy conditions. His job then became avoiding those at all costs.

In software development, we can apply the same principle. The path to becoming a great engineer isn’t about chasing trends or mastering dark and niche algorithms. You should aim for mastery in your field, but systematically identifying and eliminating the habits that produce mediocre, unmaintainable, and value-destroying code is way more impactful.

With that in mind, let’s diagnose the problem.

The Anatomy of a Mediocre Engineer

Mediocrity rarely comes from a single fatal flaw; it is more a collection of habits and bad decisions that compound over time. Here are some of the most damaging ones for a developer:

1. The Clever Coder

- They think smart hacks, fewer lines of code, and over-engineered approaches are a sign of higher skills. They code solutions that no one can understand, including themselves a few weeks later.

- They prematurely optimize code that isn’t a bottleneck or a problem for anyone, wasting days on a problem that doesn’t exist.

- They over-engineer for a hypothetical future, building systems to “scale” for millions of users when the product has a hundred.

2. The Disconnected Coder

- They don’t think or care about the relation between technical work and user value. They never ask “why,” so if a requirement makes no sense, they build it anyway.

- They work in isolation, collaborating with the rest of the team only if extremely necessary. They miss out on feedback loops, knowledge exchange, etc.

3. The Mechanical Coder

- They are ticket-translators, not engineers. They build exactly what is asked, never questioning assumptions, suggesting better alternatives, or complements—even when they know that the current approach won’t work. They follow orders and avoid all friction.

4. The Finger-Pointer Coder

- They treat quality, testing, and security as someone else’s problem. Their code works on their machine, and that’s enough.

- They deflect all blame. When a problem appears, their first instinct is to show that it is not on them rather than working toward fixing the problem.

5. The Comfort-Zone Coder

- They take shortcuts, knowingly creating technical debt, even when they are not forced by a delivery or deadline.

- They treat their tech stack as a silver bullet, using it for every problem regardless of whether it’s the right tool for the job.

- They stop learning the moment they feel comfortable in their role, their skills slowly becoming outdated.

The Solution: Putting Inversion to Work

Now that we’ve identified the enemy, let’s see what steps, frameworks, and mindsets can defeat it.

1. Write Dumb Code

Clarity is the primary goal. Write code that is so simple, clean, boring, and predictable that any new team member can understand it.

- Leave clever hacks for emergencies, and document them in detail so anyone can work with them later on, yourself included.

- Optimize only what is known to be a problem, do not waste resources in cases that are acceptable as they are.

- Leave all code you touch cleaner than you found it. Continuous, small refactoring is more manageable and better than big changes all at once.

2. Also be a Product Engineer

Your job is not only to write code, it’s also to deliver value for the end user.

- Ask “why” before writing anything. Understand the business goal behind every task.

- Communicate constantly and clearly, share context, ask for early feedback. Be someone people like working with.

- Think like an owner. Your job is not just to write good code, it is to make sure that the product succeeds. Align your work with the high-level goals.

3. Own Everything

Take ownership of the entire development lifecycle. The code you ship is a reflection of your professional standards.

- Treat testing and security as your responsibility. If the code fails it is on you, so learn the basics of these fields and apply them every day.

- When something breaks, fixing it comes first. You shouldn’t take on the blame for others but that can be clearer after the problem is solved.

4. Solve the Right Problem

Your true value lies in your ability to think critically and solve problems.

- Challenge requirements, respectfully. If a request seems too complex or nonsensical, question it until you understand the root problem or they insist on it even knowing the implications.

- Propose better solutions. If you see a simpler or better way, make the case and present the trade-offs.

- Document all decisions. Leave a trail of your thinking and discussions in pull requests or documentation. This helps everyone understand why something was done that way, and also covers your back for the worst-case scenarios.

5. Stay Curious

We should always keep learning, but in this fast-changing tech world we must choose where to invest our time carefully.

- Be pragmatic, distinguish hype from substance. Understand what problems a new tool actually solves and if it is something relevant for you.

- Use the right tool for the job, even if it’s not your favorite. Be honest about the limitations of your current tech stack.

- Do basic research on general topics and how to solve a given problem; most of the time it is enough to know that certain solutions and tools exist. If you ever need them, you can then deep dive.

Final Thoughts & Actionable Advice

Becoming a great engineer is a process of deliberate habit-building. Instead of aiming for the moving target of greatness, INVERT; focus on achievable and trackable goals that ensure you are being consistently not terrible.

Stop thinking and start doing. Here’s how you can apply this today:

- Define your anti-goals. On your next or current project, write down the top three ways it could fail, define how to avoid them, and make those your top priorities.

- Make clarity your #1 metric. During your next code review, ask: “Could a junior understand this with minimal help?” If the answer is no, it probably can and should be simplified.

- Own a system. Pick one area of your team’s codebase, ideally one you frequently work with, and become its designated expert. Take full responsibility for its quality, testing, and documentation. Remember to talk this with the team so you don’t step on anyone’s toes.

“All I want to know is where I’m going to die so I’ll never go there.” - Charlie Munger

Images generated by Google Gemini, Thumbnail inspired by UNO Reverse Card.